Whether you’re an architect or a construction manager, perfection is everything. This line of work is one of the few where lives hinge on decision makers’ foresight and expertise. So, if perfection is the name of the game in the design-build world, why is it so hard to achieve?

Looking at the research available, two major signposts point to answers: a complex design process resistant to digital transformation and an epidemic of inaccurate product data. Ultimately, building product manufacturers’ hesitation to embrace a changing market stains the attitudes of AECs dependent on their products. This fear of innovation comes at a significant price—literally. All parties in the build-design process face an ongoing congestion in productivity and profits. How did the industry get into this rut? And, more importantly, why are manufacturers refusing to embrace change?

At Concora, we want to help manufacturers improve the workflows of their AEC customers. Especially in the commercial construction field, time wasted is money wasted. Any manufacturer ignoring the concerns of productivity for their clients wastes an opportunity to become a champion for those clients and ultimately build brand loyalty. Before we discuss how manufacturers can accomplish this, let’s first take a look at the issues facing the AEC industry’s project processes:

The Fantasy of Perfection

When asking virtually any leader in the architecture, engineering, or construction specialties, the perfect project has four main components. Ideally, the job is done:

- On-time,

- Under budget,

- With a thrilled client, and

- With a creatively challenging design

With only four ingredients to this recipe, a stellar project should be easy to whip up, right? The problem with this bird’s-eye viewpoint is its inability to see the nuance, the sheer amount of energy required to meet any one of these requirements—let alone all four.

Boiling down a perfect AEC project to its most basic outcomes is like saying a Baked Alaska is just a pile of cake and ice cream. Sure, that’s technically correct, but anyone who’s tried to create one would laugh at the description. There’s precise timing, specialized ingredients, and nuanced measurements involved. A mistake in any one of these areas would create something either tasteless, shapeless, or both. Multiply these factors by the risk and the infinite other variables in a commercial construction job, and you’ve got one complicated project on your hands.

The Reality

A project completed on time, under budget, with a thrilled client, and with a creatively challenging design is extremely rare.

Experts estimate at least 85% of construction projects go over budget. This isn’t a question of working for penny-pinching clients, either. An analysis across asset classes by researchers at McKinsey found that even large projects typically take 20% longer to complete and are 80% more expensive than initially estimated.

Some of this may point to an aversion to implementing new technologies. Although architect and designers have embraced the latest in technology, their counterparts trail behind. Construction is second only to agriculture as the least digitized workforce in today’s economy. On top of that, it remains one of the least productive industries in the world. Although it has over $10 trillion a year poured into its projects, the industry is the most stagnant in terms of productivity. In another of McKinsey’s thorough investigations of the construction industry, its researchers estimate:

While many U.S. sectors including agriculture and manufacturing have increased productivity ten to 15 times since the 1950s, the productivity of construction remains stuck at the same level as 80 years ago. Current measurements find that there has been a consistent decline in the industry’s productivity since the late 1960s.

Admittedly, productivity remains one of the most difficult economic factors to measure. But with 80 years of data to back up McKinsey’s findings, we aren’t looking at a simple slump in the AEC world. It’s a full-blown rut.

In turn, this spells trouble for product manufacturers. They’re typically removed from the finished project with little knowledge on how this lack of automation impacts the bottom line of clients. Some might view this issue as something that’s none of their concern—and that’s a big mistake.

Today, especially in the AEC industry, time is money. “Billability” is one of the biggest concerns of any firm’s accounting department. So, if structures are taking longer to build, they’re requiring more labor and therefore more money to complete. The inability for an AEC firm’s key decision makers to streamline inhibits their ability to complete ideal projects (on time and on budget).

Embracing BIM as a way for manufacturers to help streamline client workflow is as an enticing differentiator for designers. In essence, the AEC efficiency crisis creates an ocean of opportunity for manufacturers. After all, if you make the products needed for construction projects, you are in a powerful spot to change the way the job gets done.

The concerns outlined here aren’t falling on deaf ears, either. Rem Koolhaas, one of the most recognized names in architecture, recently highlighted the divisions between his industry and the breakneck speed of today’s tech advancements:

“Architecture is a profession that takes an enormous amount of time. The least architectural effort takes at least four or five or six years, and that speed is really too slow for the revolutions that are taking place.”

Although these findings are concerning, they aren’t impossible to turn around. After years of getting to know the industry from the inside, we identified one of the biggest inhibitors in the AEC workflow at large: a lack of easily accessible, accurate product data.

How can manufacturers improve the industry?

When analyzing the reasons behind the industry’s stagnation of productivity and cost efficiency, a clearer, yet complicated, picture starts to emerge.

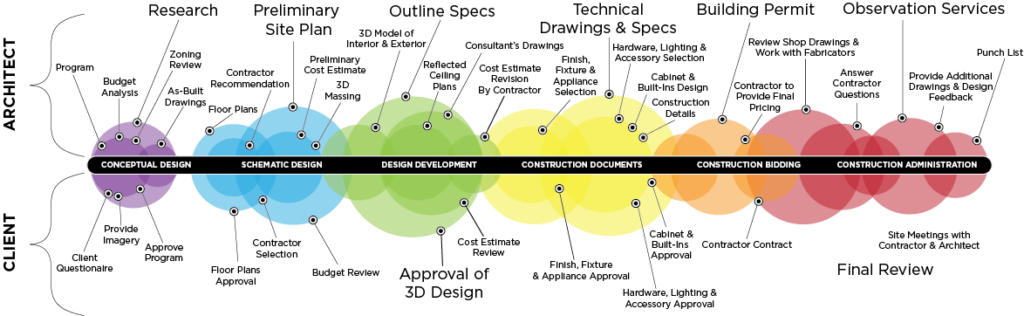

The life cycle of even the most basic of AEC projects looks like this:

Adapted from chart illustrated by HMH Architecture + Interiors

The multi-tiered, comprehensive work cycle seen here offers plenty of chances for inaccurate information to make a mess of things. In a recent AIA SmartMarket analysis on the current state of the AEC industry, architects ranked design omissions as one of the major drivers of excess cost during the course of a project. Specifically, omissions of information happen in over half (54%) of all projects, which can include gaps as significant as missing project scope after solidifying a budget.

Fixing these issues requires designers to take time away from the exciting, creative aspects of their work. Zoltan Toth, Intl. Assoc. AIA, spent several years working as an architect in both the US and Budapest. No matter the region, the balance between problem solving and actual creative design remains off-kilter.

“Architects are usually responsible for coordinating among all stakeholders… They manage relationships with clients; structural engineers; MEP engineers; landscapers; interior designers; sustainability experts; contractors; authorities; [the list goes on]. All of these different relationships require different deliverables from them, so [architects] end up producing a crazy amount of documentation during the design/construction process. This leaves little time for actually designing, which is pure creative work and requires a specific (usually relaxed) frame of mind and a lot of time.”

So, in an effort to stay on schedule and on budget in the face of inaccurate information, time for creativity suffers. Mitigating unrealistic client expectations also accounts for funding shake-ups. A whopping 63% of architects cite owner-driven program changes as one of the top causes of uncertainty in a project. Trying to please a client ends up costing further money and time while in the throes of the design process. When trying to balance client satisfaction, creative work, budget, and scheduling into a perfect project, you start to realize these things aren’t exactly complimentary.

In reality, the qualities of a perfect project don’t exist in harmony—they’re at war with one another. But, that doesn’t mean the AEC industry needs to surrender to this current state of affairs. Product manufacturers can lead the charge for their clients and finally break the cycle.

Standardized Communication

Any aspiring life coach worth their weight in Twitter followers can tell you conflicting goals aren’t a sign of failure. They’re a sign of potential. Meaning that for AEC’s key decision makers, there just might be a way to have it all.

Looking at the root causes of issues with time, money, creativity, and client satisfaction, information accuracy and communication are two of the biggest players. But, there isn’t something necessarily inherent to this industry that renders change impossible. Getting owners, engineers, consultants, and construction managers on board with a project in its planning stages has shown to improve expectations, reduce the frequency of scope errors, save time, and save money. Better collaboration can be difficult, especially when standard methods of communication are hard to come by. Some people prefer email, some texting, others prefer a phone call. So much can get lost in translation when trying to unify messages sent through such radically different channels. What if there was a centralized portal that provides transparency and accuracy to the design process for all parties? Some may point to BIM as this sort of Rosetta Stone for communication in the AEC industry. After all, it is considered the standard program for modelling projects of virtually any complexity. Jim Austin, Concora’s Senior Program Manager, notes that currently, “85-95% of projects with a budget of $11 million or higher are delivered using BIM.” Standardization within this program, however, remains as elusive as an HD photo of Bigfoot.

As an architect, Toth champions the usefulness of BIM for both manufacturers and AECs. “Agreeing on adopting standards or a well-written BIM Execution Plan can massively speed up the process, versus trying to invent the whole thing on the fly,” he said. Project managers need to lead the charge in making sure the whole team knows how to input data from the beginning, since BIM’s flexibility can ultimately be a huge liability for the entire team.

Accurate, Up-to-Date Product Data

Like a skyscraper, standardized communication is only as stable as its foundation. But, instead of rebar and tons of concrete, it requires accurate product data. Some of this requires simple measures like a robust knowledge of BIM. This knowledge, however, means nothing if the data put into the program is wrong. A study conducted at Concora discovered that 47% of architects cited problems with finding up-to-date technical product data for Revit.

Additionally, according to analysis from researchers at the University of Kentucky, fixing design flaws has a huge impact on the bottom line.

In a typical construction development project which involves design and construction, rework in the construction phase could increase construction cost[s] by 10%-15% of the contract price… In large, complex projects, undiscovered rework in the design phase can induce rework in the construction phase. The time when rework is discovered during the project development process affects the impact of rework on overall project performance.

Without good information, you can’t reasonably estimate scope and therefore can’t provide realistic expectations not only to clients but also to fellow team members. While some of this could boil down to poor programming execution, it’s certainly also due to the quality of the Revit files provided by manufacturers. Since product Revit files are the crux of any BIM model, it begs the question:

Is it possible that manufacturers are to blame?

The Fear of Change Starts (and Stops) with Manufacturers

If time is money for architects, engineers, and construction managers, manufacturers must prioritize easy access to accurate information. In fact, experts cited in an Architect Magazine piece note that the best way for a manufacturer to serve potential clients is to pose as a trusted resource for specification needs. Reliability matters, especially in an industry as people-driven as commercial construction.

An in-depth investigation published by the American Institute of Architects also highlights these findings. (An executive summary is available for free here.)

“9 in 10 manufacturers believe their organization would benefit from a greater focus on architects. Manufacturers who want to grow their specifications need an architect engagement strategy that is based on rethinking the two primary touchpoints through which they engage with architects: reps and websites.”

Architects, and let’s be honest, everyone who hasn’t lived under a rock for the past two decades, heavily rely on websites to learn about products. These days, a web address is much more than a place to publish contact info—it’s the first step towards building a trusted relationship. In addition to knowing the ins and outs of BIM, Concora’s Austin also notes the pivotal importance of understanding AEC expectations in the manufacturing world. Simply put, “if you’re not dynamically involved with your clients and in your respective market, you’ll starve.”

Providing a real-time, accurate Revit resource to potential and current buyers is key to manufacturer success—and the success of their AEC customers. At Concora, we are leading the way in the development of tools that are both AEC and manufacturer friendly. Our platform enables manufacturers to better serve the needs of the architects, designers, and speculators that visit their websites in search of reliable product data. The important information AECs need to keep a project rolling is easy to find and download, cutting down time spent on sourcing materials and eliminating the uncomfortably common possibility of incorrect or out-of-date data causing money-wasting delays down the road. A process as complex as designing and constructing a commercial building may never be “perfect,” but when all parties can agree to embrace digital transformation instead of running from it, there’s nowhere to go but up.